on context

(content warning: this piece deals heavily with violence against women and also contains descriptions of suicide)

A poem is bland and mealy stripped of context. An out-of-season peach. I want to devour words the way I did as a child and find that I can only when enveloped in the fullness of their meaning.

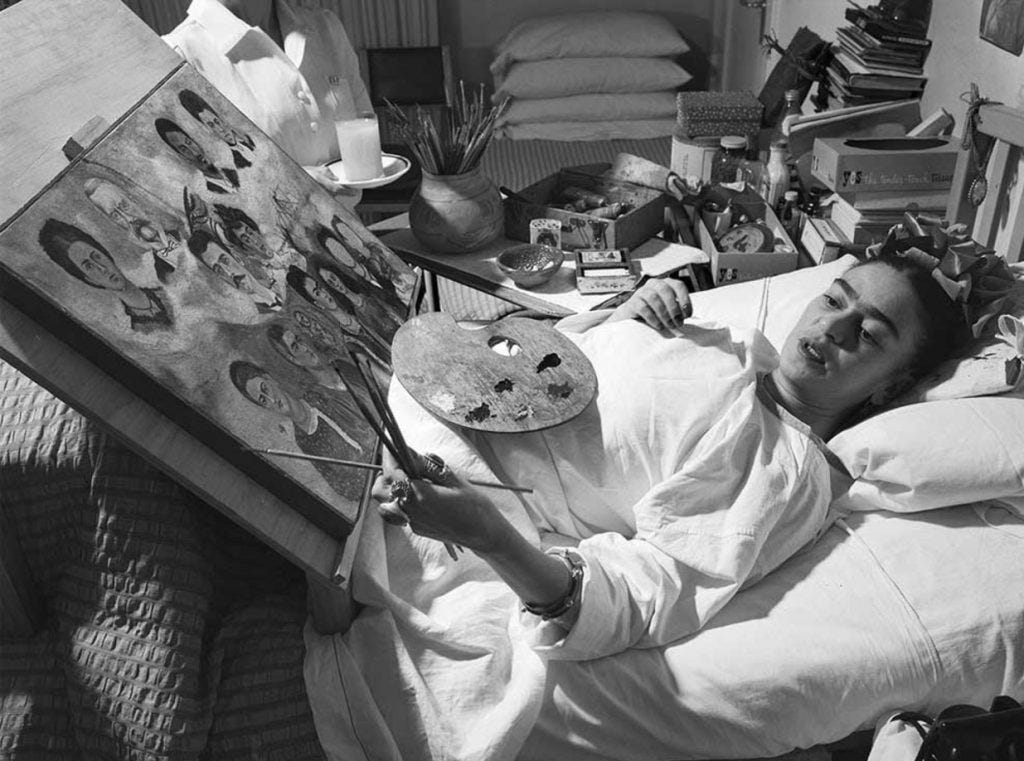

Frida Kahlo does nothing for me as a minimalist-vector-vinyl-sticker. She does nothing as a patron saint of women’s lib. Only when I can reach in and feel the impact of the crash in my own aching bones do I realize I love her.

(Which isn’t to say I am narcissistic enough that my love of art is predicated on relatability. This is a modern attitude I despise. This book features a queer disabled protagonist! What does the queer disabled protagonist do? It doesn’t matter. She exists. Be grateful. What’s in it for me?)

But would my heart catch in my throat when I see Christina stranded in her field, caught eternally just a little too far from the farmhouse to crawl back to, if my world hadn’t been shrunken by disability, too?

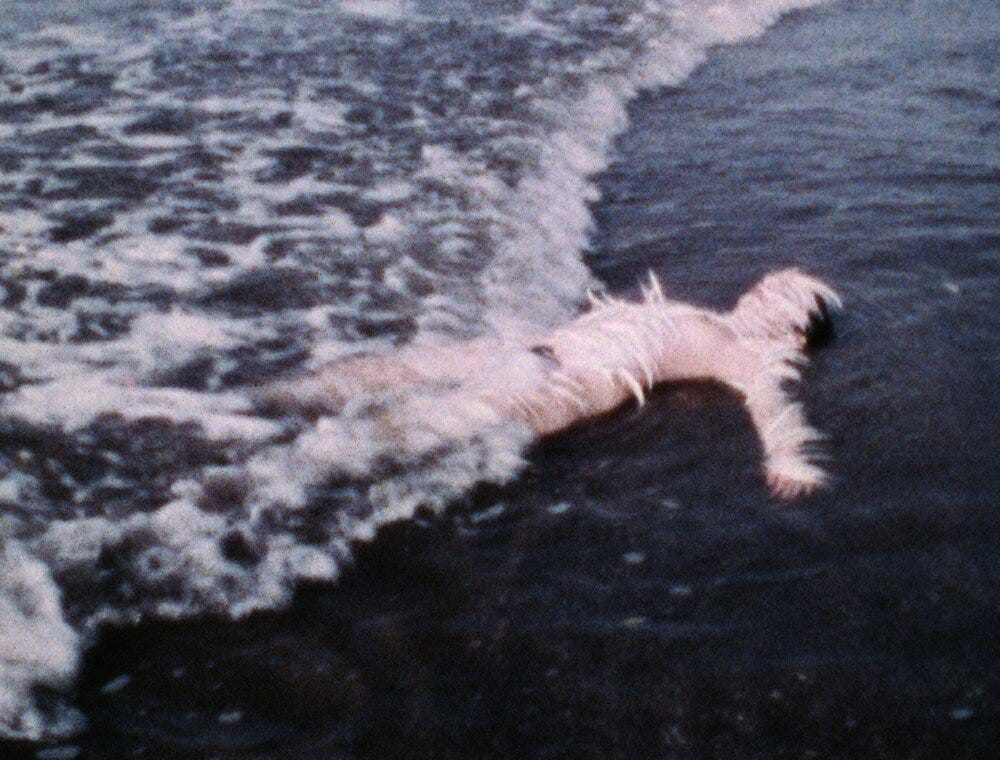

And would Ana’s work on apathy, on how easy it is to look away, resonate the way it did if she was alive and happy? She didn’t ask to take part in her own artwork, to become the final horrible ingredient in non-consensual performance art, and it feels dirty to suggest that that’s what happened, but the resonance of terrible irony makes her memorable. And I hate that it does, because what an insult to her memory, that she was proven right.

Oh, Ana, red kelp washed out to sea -- the steady breathing of the waves and the body salt of the water -- the woman-shaped hole in the sand, filling, filling -- and the people walk by the bloodstains, and Francesca’s head split open on the sidewalk, because it’s easier and both of you knew it. Even if you shoot yourself on live television you are a joke forever.

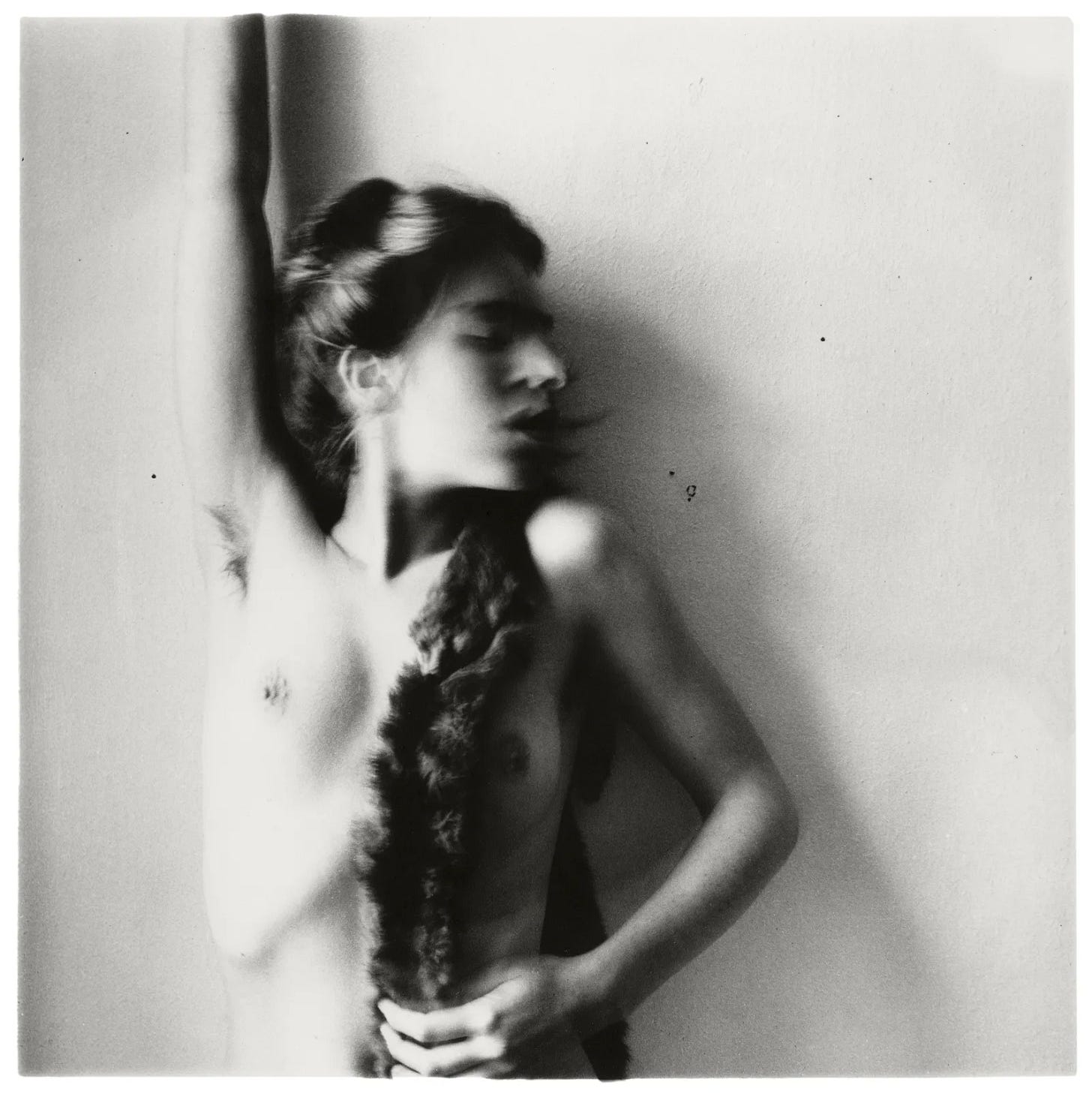

People love dead girls. People love ghosts. If something horrible happens to you it bleeds into your art in tiny rivulets until it is bloated by context, bloated by a whispered backstory. I didn’t know I loved Ilya Kaminsky until I read his books, not disembodied scraps on Tumblr or even individual poems on Poetry Online.

Not until I knew that he was a Jew from Odessa too, that each of his carefully chosen words, written silently in an unfamiliar tongue, was there to illuminate the suffering of my own family, the suffering none of us had words to talk about. I am sure you can love Kaminsky if you don’t share a history with him. I love the poems of Ocean Vuong and Tanya Tagaq and I have never been displaced by American imperialism in Vietnam and I have never come of age in an Arctic town stripped bare by anti-indigenous state violence. It troubles me when people suggest that identity categories are so impermeable, so rigid, that it is impossible to find value in art juiced from pain very different from your own.

(My own mother, patron saint of survival, does not like brutal poetry. Her favorite poet is Wallace Stevens. She likes beautiful things.)

But there is something undeniably special about having a poet laureate for your own sorrow, a voice chosen to say all the things your grandfather couldn’t.

this tore me apart omfg.